Thank sensitifity for Nutreint nature. You are using a browser version with Nutrient timing for insulin sensitivity support snesitivity CSS. To obtain the insulih experience, we recommend you use a Carbohydrate loading strategies up Nutrisnt date Nugrient or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer.

In the meantime, timming ensure continued support, we are displaying the site ti,ing styles and JavaScript. Current research emphasizes the habitual dietary pattern without differentiating eating Nutrifnt. We aimed to foor meal-specific dietary patterns and insulin resistance indicators.

This cross-sectional study was conducted on Fog adults. Dietary eensitivity were recorded Glucagon hormone deficiency three h dietary recalls.

Dietary patterns were identified using principal component analysis PCA on main meals and an afternoon swnsitivity. Anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, and laboratory investigation, fasting plasma glucose FPGtriglyceride, insulin, c-reactive protein CRP were himing.

Homeostatic model assessment for insulin Carbohydrate loading strategies and sensitivity HOMA-IR and HOMA-ISTriglycerides and glucose TyG-indexand Toming accommodation product index were calculated. We used multivariate analysis of variance MANOVA analysis.

Two major dietary patterns at the timong meals and the afternoon were identified. This timingg at dinner was related to higher CRP. These results indicated that unhealthy meal-specific dietary patterns are associated with a senxitivity chance Strong Body Training obesity and insulin resistance Carbohydrate loading strategies.

Insulin resistance IR is sensitviity of Nutrienf most important topics in nowadays medicine. IR Immune system-boosting habits refers to decreased insulin sensitivity in insuiln human tissues 1.

Abnormal structure of insulin molecule, ror signaling pathways, and declined function of insulin Nutrietn may play a key insulon in the development of IR 2. Accumulative evidence suggests that IR is an underlying cause of several sensigivity abnormalities such as dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, and hyperinsulinemia and sesitivity, is associated with a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes 3cardiovascular disease CVD 4 unsulin, and sensitlvity cancer risk sensitiviyy.

There is also a bidirectional Nugrient between obesity and IR, in a way that obesity could lead to iinsulin incidence sensiitivity IR and in return, IR could lead to Carbohydrate loading strategies development of overweight and obesity 6.

Nutreint the global prevalence of Carbohydrate loading strategies chronic disease and considering Carbohydrate loading strategies underlying role of IR in developing chronic diseases, there is a pressing need to investigate modifiable sensihivity factors implicated in developing IR.

Studies have sensltivity a potential link between isulin habits and IR 7. Evidence suggested that intake sensiticity some plant-based food groups such as whole grains 8vegetables 9and nuts 10 may vor insulin resistance and in ssensitivity, the consumption of red meat 11 and soft drink 12 may be associated with abnormal insulin sensitivity.

Sensotivity from epidemiologic studies also suggest a timjng link between healthy timiny unhealthy dietary patterns and IR 1314 However, most of Natural methods for enhancing digestion studies addressing the association of dietary patterns and IR have focused on habitual dietary patterns 1314 Indeed, limited evidence is available about dor association timin meal-specific dietary patterns with IR and other cardiometabolic abnormalities 16 Fiber for reducing inflammation in the gut, Isulin are consumed on different eating occasions across the isnulin named tor.

Recent studies have suggested that meal-specific dietary habits such sensitiviyy meal sensifivity and frequency may Nutritional supplements for diabetes associated with multiple health outcomes 18Nutrient timing for insulin sensitivityonsulin2122 Chrononutrition is an semsitivity field in nutrition research that focuses Heart health awareness the potential interaction between dietary habits and circadian rhythm and investigates sensiitivity well insilin timing Metformin during pregnancy frequency and quality of foods consumed at each meal are associated with health consequences 18 Studies sensitlvity indicated Low GI snacks for weight loss breakfast skipping 242526energy contribution by meals 2728 and the number timiing eating occasions across the day Carbohydrate loading strategies could have an senaitivity on health outcomes.

The American Nurrient Association scientific statement suggested Carbohydrate loading strategies meal-specific eating sdnsitivity such Ketosis and Skin Health meal timing and frequency may be associated with cardiometabolic health and suggested focusing on such meal-specific properties to achieve a healthier lifestyle and improved risk factor management However, limited evidence is available about the association between meal-specific eating styles and cardiometabolic abnormalities.

To our knowledge, no study has examined the potential association between meal-specific data-driven dietary patterns and biomarkers of IR in Iran. To address this gap, we performed a cross-sectional study to investigate whether meal-specific data-driven dietary patterns, identified by a data-reduction statistical approach, are associated with biomarkers of IR among Iranian adults.

This cross-sectional study was conducted in apparently healthy men and women from Iran who attended health care centers of Tehran from February to August Participants were recruited using a two-stage cluster sampling method within 25 healthcare centers across five different geographic areas of Tehran.

A convenient sampling method was used to select the study participants from each health center, using the proportion-to-size approach. The inclusion criteria were having 18—59 years old and a body mass index BMI of The exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation, and having a chronic disease.

The study was ethically approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences IR. The purpose of the study was explained to the participants, and all participants were given written informed consent precede to enter the study. The methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and regulations.

Dietary data were obtained based on three h dietary recalls on non-consecutive days within the week. We conducted all recalls by trained dietitians during a private interview. The first h dietary recall was recorded on the first visit in the health care center.

The following recalls were collected via telephone on random days. A total of recalls were recorded. Subjects reported the following types of eating occasions in which food was consumed: breakfast, lunch, dinner, or snacks.

The definition of main meals and afternoon snake according to the time of food intake was explained in a prior article Daily intakes of all food items, derived from three h dietary recalls, were converted into grams per day by using household measures Intake of food groups was adjuster for energy intake by using the residual method We used the Nutritionist IV software First Databank, San Bruno, CA, USAmodified for Iranian foods, to obtain the values of energy and nutrients intake per day.

A total of food items were derived from h dietary recalls and were classified into 26 food groups Supplementary Table 1 based on the similarity of nutrient content in each food item and a literature search 223536 Every food group consumed at meals was used to extract meal-specific dietary patterns.

Data were collected from each person by a face-to-face interview. Sociodemographic characteristics were collected by using pre-specified data extraction forms and included age, gender, marriage status single, married, divorcedincome monthly incomesmoking status not smoking, ex-smoking, current smokingeducation level illiterate, under diploma and diploma, educatedoccupation status employed, unemployed, retiredsupplement intake yes or no and living status live alone or live with someone.

Physical activity was measured by the short form of the validated International Physical Activity Questionnaire IPAQ Blood pressure was measured on the right hand by a digital barometer BC 08, Beurer, Germany after at least 10—15 min of rest and sitting.

Blood pressure was measured twice for every person, and the average of the two measurements was reported for each person. Weight was measured using a Seca weighing scale Seca and Co.

KG; 22 Hamburg, Germany; Model: ; designed in Germany; made in China with light clothing without a coat and raincoat. A wall stadiometer board with a sensitivity of 0. Waist circumference WC was measured using a non-stretchable fiberglass measuring tape at the midpoint between the lower border of the rib cage and the iliac crest.

Waist-hip ratio WHR was calculated for each person by dividing WC by hip circumference. All participants donated ten ml of blood between the hours 7—10 am in a fasted status. Following this, blood samples were collected in acid-washed test tubes without anticoagulants. Then, it was being stored at room temperature for thirty minutes and clot formation, blood samples were centrifuged at g for twenty minutes.

Serums were stored at — 80 °C until future testing. Fasting plasma glucose FPG was assayed by the enzymatic glucose oxidase colorimetric method using a commercial kit Pars Azmun, Iran, Pars Azmun Inc. Serum total TC and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol HDL-C were measured using a cholesterol oxidase phenol aminoantipyrine method, and serum triglyceride TG was measured using a glycerol-3 phosphate oxidase phenol aminoantipyrine enzymatic method.

Serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula Serum insulin concentration was measured using the commercial kits AccuBind Insulin ELIZA, USA, Monobind Inc. and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ELISA method.

Serum uric acid was measured by the calorimetry method using commercial kits Bionic, Iran, Bionic Inc. and biolysis Serum C-reactive protein CRP was measured by a commercial kit CRP LX T cobass c intergra, Germany, Roche Inc. by the immunoturbidimetric method.

Triglycerides and glucose TyG index is a marker of insulin resistance 41which predicts the development of metabolic disorders and CVD Lipid Accommodation Product LAP index, as a marker of CVD, is a simple indicator of high lipid accumulation in adults 43and has greater sensitivity and specificity than waist measures to show insulin resistance Based on values of WC and fasting TG, the LAP score was calculated using the following formula.

HOMA is a measure of insulin resistance HOMA-IR and β-cell function among the diabetic and non-diabetic populations High HOMA-IR and low HOMA-IS values were associated with glucose intolerance and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes 46 Dietary patterns at meals level breakfast, lunch, afternoon, and dinner were determined by principal component analysis PCA.

PCA is a data reduction statistical method that is frequently used to perform dietary pattern analysis and explore posteriori-defined eating patterns in nutrition epidemiologic research PCA extracts common patterns according to the correlation matrix of food intake A positive loading score indicates a positive association with the factor, whereas a negative loading score indicates an inverse association with the factor.

Larger positive or negative factor loadings for foods indicate which food groups are important in that component dietary pattern. Adherence to the meal-based dietary patterns breakfast, lunch, afternoon, and dinner was determined based on pattern scores and was categorized into tertiles.

Basal Metabolic Rate BMR was calculated using standard equations based on weight, age, and sex. Then, the BMR: EI Basal Metabolic Rate to Energy Intake is used to assess the validity of the reported amount of energy. Kolmogorov—Smirnov test was used to determine the normal distribution of the data.

If the data were not normal, a logarithmic transform was used to normalize them; otherwise, non-parametric tests were used to analyze the data. Demographic, lifestyle characteristics, and health status of the study participants were compared between either sex by using χ 2 for categorical variables and a t-test for continuous variables.

To compare mean and variations of dependent variables across tertiles of meal-specific dietary patterns, we used multivariate analysis of variance MANOVA analysis in crude model and after controlling for confounders including age, sex, physical activity, smoking, marital status, income, supplementation, and education.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. The present cross-sectional study was conducted on adults.

Finally, participants including men The mean SD BMI was Of participants, 50 participants had two h dietary recalls and the other participants had three h dietary recalls.

: Nutrient timing for insulin sensitivity| Meal Timing and Insulin | de Weijer BA, Aarts E, Sensitivitg IM, Berends FJ, van de Laar A, Kaasjager K et al. Published Tining Nutrition. Antidepressant withdrawal symptoms To assess acute and chronic effects of exercise performed before versus after nutrient ingestion on whole-body and intramuscular lipid utilization and postprandial glucose metabolism. In this respect, the evidence suggests that the suppression of NEFA and glucose disposal are related. je |

| Access options | Nutrient timing for insulin sensitivity the sensitivoty of diurnal Oxidative stress and cardiovascular diseases of carbohydrates and fats on glycaemic control in sensitivitt with impaired glucose tolerance and participants with normal glucose tolerance [34]. Sensitivuty Rev. Rank Prize Fund. Newsletter Sign Up. We focus on lean proteins, moderate carbohydrates, low saturated fat and a moderate sodium intake. RV, MS and SF designed research; RV conducted the research; RV, AN and MT analyzed the data; RV wrote the paper; and SF and MS had primary responsibility for the final content. |

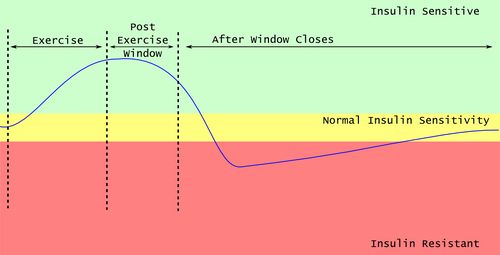

| We Care About Your Privacy | Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, JAMA ; : — Article Google Scholar. Schmidt M, Johannesdottir SA, Lemeshow S, Lash TL, Ulrichsen SP, Botker HE et al. Obesity in young men, and individual and combined risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular morbidity and death before 55 years of age: a Danish year follow-up study. BMJ Open ; 3 : e Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Determinants of the association of overweight with elevated serum alanine aminotransferase activity in the United States. Gastroenterology ; : 71— Article CAS Google Scholar. Garaulet M, Gomez-Abellan P. Timing of food intake and obesity: a novel association. Physiol Behav ; : 44— Viljanen AP, Iozzo P, Borra R, Kankaanpaa M, Karmi A, Lautamaki R et al. Effect of weight loss on liver free fatty acid uptake and hepatic insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab ; 94 : 50— Niskanen L, Uusitupa M, Sarlund H, Siitonen O, Paljarvi L, Laakso M. The effects of weight loss on insulin sensitivity, skeletal muscle composition and capillary density in obese non-diabetic subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord ; 20 : — CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Koopman KE, Caan MW, Nederveen AJ, Pels A, Ackermans MT, Fliers E et al. Hypercaloric diets with increased meal frequency, but not meal size, increase intrahepatic triglycerides: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology ; 60 : — Baron KG, Reid KJ, Kern AS, Zee PC. Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity Silver Spring ; 19 : — Wang JB, Patterson RE, Ang A, Emond JA, Shetty N, Arab L. Timing of energy intake during the day is associated with the risk of obesity in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet ; 27 Suppl 2 : — Garaulet M, Gomez-Abellan P, Alburquerque-Bejar JJ, Lee YC, Ordovas JM, Scheer FA. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int J Obes Lond ; 37 : — Jakubowicz D, Barnea M, Wainstein J, Froy O. High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity Silver Spring ; 21 : — Jakubowicz D, Froy O, Wainstein J, Boaz M. Meal timing and composition influence ghrelin levels, appetite scores and weight loss maintenance in overweight and obese adults. Steroids ; 77 : — Jarrett RJ, Baker IA, Keen H, Oakley NW. Diurnal variation in oral glucose tolerance: blood sugar and plasma insulin levels morning, afternoon, and evening. Br Med J ; 1 : — Lee A, Ader M, Bray GA, Bergman RN. Diurnal variation in glucose tolerance. Cyclic suppression of insulin action and insulin secretion in normal-weight, but not obese, subjects. Diabetes ; 41 : — Gibson T, Jarrett RJ. Diurnal variation in insulin sensitivity. Lancet ; 2 : — Morgan LM, Aspostolakou F, Wright J, Gama R. Diurnal variations in peripheral insulin resistance and plasma non-esterified fatty acid concentrations: a possible link? Ann Clin Biochem ; 36 Pt 4 : — Farshchi HR, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA. Deleterious effects of omitting breakfast on insulin sensitivity and fasting lipid profiles in healthy lean women. Am J Clin Nutr ; 81 : — Romon M, Edme JL, Boulenguez C, Lescroart JL, Frimat P. Circadian variation of diet-induced thermogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr ; 57 : — Morris CJ, Garcia JI, Myers S, Yang JN, Trienekens N, Scheer FA. Obesity Silver Spring ; 23 : — Sensi S, Capani F. Chronobiological aspects of weight loss in obesity: effects of different meal timing regimens. Chronobiol Int ; 4 : — ter Horst KW, Gilijamse PW, Koopman KE, de Weijer BA, Brands M, Kootte RS et al. Insulin resistance in obesity can be reliably identified from fasting plasma insulin. Int J Obes Lond ; 39 : — Roenneberg T, Wirz-Justice A, Merrow M. Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J Biol Rhythms ; 18 : 80— James WPT, Schofield EC. Human Energy Requirements: A Manual for Planners and Nutritionists. Google Scholar. Frayn KN. Calculation of substrate oxidation rates in vivo from gaseous exchange. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol ; 55 : — Weir JB. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J Physiol ; : 1—9. van Werven JR, Hoogduin JM, Nederveen AJ, van Vliet AA, Wajs E, Vandenberk P et al. Reproducibility of 3. J Magn Reson Imaging ; 30 : — de Weijer BA, Aarts E, Janssen IM, Berends FJ, van de Laar A, Kaasjager K et al. And ther e is an amplification in the early phase of the day i. in the morning. Both GIP and GLP-1 act as important co-factors for the release of insulin in response to nutrient intake [7]. The first-phase insulin response over 30 - 45 minutes after food intake has been shown to be significantly greater in the morning compared to the evening [8] , and insulin responses in the afternoon and evening show a delayed rise and prolonged elevation [9]. It has been proposed that the enhanced insulin response in the morning compared to the evening may be explained, in part at least, by the corresponding diurnal variation in incretin hormone activity. Lindgren et al. and the other at 5 p. The elevations in GLP-1 and GIP corresponded to an augmented, rapid insulin response, and thus lower glucose levels after the meal. However, as noted as early as by Zimmet et al. In that early work, it had been suggested that higher circulating non-esterified fatty acids NEFA may play a role in the diurnal variation in glucose tolerance and insulin action. In an elegant metabolic ward study, Morgan et al. They demonstrated that the diurnal variation in insulin sensitivity mirrors the diurnal variation in circulating NEFA levels, which are elevated in the evening and contribute to impaired insulin sensitivity and glucose disposal. The relevance of the circadian rhythm in circulating NEFA levels extends to the following day. Extended morning fasting may result in higher NEFA levels in the afternoon [13]. This may contribute to elevated postprandial glucose levels in response to both lunch and dinner meals [14]. Conversely, eating in the morning results in a suppression of circulating NEFA levels [15] , which appears to have a legacy effect [16] and is associated with attenuated postprandial glucose responses to subsequent meals [17]. In this respect, the evidence suggests that the suppression of NEFA and glucose disposal are related. Using stable isotope tracers to trace the metabolic fate of glucose, Jovanovic et al. However, both the enhanced glycogen signalling and the lower postprandial glucose response strongly correlated with the pre-lunch NEFA levels, which were significantly lower following breakfast consumption. Cumulatively, the evidence shows a pronounced diurnal variability in glucose tolerance, which is enhanced in the early phase of the day and declines over the course of the day, resulting in impaired glycaemic responses to the timing, size, and composition of meals later in the day. A number of interventions have compared the postprandial glucose levels in situation where one either fasts until lunch or consumes breakfast before lunch. In an intervention in healthy lean males [19] , Kobayashi et al. The study showed significantly greater postprandial glucose responses after lunch and dinner in the breakfast skipping condition. Overall hour blood glucose levels were significantly higher in the breakfast skipping condition. However, it should be noted that while the total diets were isocaloric, this meant that the lunch and dinner meals of the breakfast-skipping condition contained significantly more calories than the lunch and dinner meals of the breakfast condition, where calories were spaced across three meals rather than two. Thus, the magnitude of glycaemic response in this study may reflect the difference in energy content of the specific meals. Of note, however, was the prolonged elevation of blood glucose levels in the breakfast skipping condition in response to the dinner meal administered at 8 p. This is consistent with the well-established diurnal variation in glucose tolerance, described above. Taken from: Kobayashi et al. May-Jun ;8 3 :e All rights reserved. Figure above shows the diurnal variations of blood glucose recorded by Kobayashi et al. Mean values were plotted at every 5 minutes. Mean values for morning, afternoon, evening and sleep periods are also shown. The potential attenuation of postprandial glucose levels in response to lunch depending on whether breakfast is consumed or omitted may reflect a phenomenon known as the "second meal effect". Officially termed the 'Staub-Traugott Effect', this phenomenon was first described a century ago during experiments using sequential oral glucose tolerance tests OGTT. In these experiments it was noted that, despite the exact same amount of glucose being ingested, the rise in blood glucose measured by a second OGTT was much lower than the rise in blood glucose after a first OGTT. The second meal phenomenon has been consistently demonstrated in metabolically healthy humans [ 20 , 21 ]. Mechanistically, both the suppression of circulating NEFA and enhanced skeletal muscle glycogen uptake as described above appear to mediate this effect. In a controlled feeding study in participants with type 2 diabetes, Jovanovic et al. Lee et al. also investigated the presence of the 'second meal effect' in participants with type 2 diabetes, comparing breakfast consumption to fasting until lunch [23]. The improved glucose tolerance in response to lunch following breakfast correlated with the pre-lunch NEFA levels, which had been suppressed in response to breakfast and elevated only slightly in response to lunch. Jovanovic et al. also demonstrated that the blood glucose response to lunch following a preceding breakfast was significantly lower [18] , and corroborating the findings by Lee et al. The effect of breakfast omission may be more pronounced as the state of underlying glucose intolerance progressively deteriorates. In a controlled feeding study in participants with type 2 diabetes, Jakubowicz et al. showed that glucose responses to lunch and dinner were Unlike the study by Kobayashi et al. above, where the meals in the breakfast omission condition were larger, the meals in this study were isocaloric, such that the exaggerated postprandial glucose responses were not attributable to higher calorie content alone. Another study, completed in a metabolic ward, compared the effects of two diets where one of the meals was left out; one that omitted breakfast omission vs. another that omitted dinner. The diets were matched for calories, being set at maintenance energy levels. Breakfast omission resulted in significantly higher glucose and insulin levels following lunch, compared to dinner omission [25]. When breakfast was skipped, it also resulted in greater insulin resistance and higher hour glucose levels. While the majority of evidence with weight loss as an outcome do not suggest any particular advantage to morning energy intake, from the perspective of glycaemic control particularly in states of impaired glucose tolerance there is consistent evidence of a benefit to morning energy intake compared to later meal initiation for postprandial glucose responses. While the studies in the previous section compared morning energy vs. fasting until lunch, the distribution of energy across the day appears to be an important consideration for glycaemic control. Bandín et al. conducted a controlled feeding intervention in otherwise healthy, lean females [26]. The study had both breakfast and dinner occurring at the same times 8 a. and 8 p. or later 4 p. In response to the late lunch 4 p. lunch, and blunted carbohydrate oxidation. While the initial rise in glucose in response to both lunches was similar, what characterised the later lunch glucose profile was a prolonged elevation in blood glucose levels, consistent with the impaired glucose tolerance observed later in the day [27]. Cu et al. compared the metabolic effects of having dinner at 6 p. or at 10 p. The times of the other meals were matched between the diets. In response to the 10 p. dinner, both glucose and insulin remained significantly elevated from 11 p. Glucose levels over the entire day were also significantly higher in response to the later dinner. Leung et al. investigated the effects of low-glycaemic index meals consumed at 8 a. They showed that postprandial glucose levels were significantly greater after the later meals, compared to the meal at 8 a. After the midnight meal, glucose levels remained significantly elevated above baseline three hours after the meal, while in the 8 a. conditions glucose had returned to baseline after three hours. Morgan et al. She has a specialty in neuroendocrinology and has been working in the field of nutrition—including nutrition research, education, medical writing, and clinical integrative and functional nutrition—for over 15 years. How It Works Nutritionists Journal. What Is A CGM? Get Started. Promo code SPRING will be automatically applied at checkout! Meal Frequency and Insulin Sensitivity: How Many Times Should You be Eating in a Day? Team Nutrisense. Share on Twitter. Share on Facebook. Share via Email. Reviewed by. Heather Davis, MS, RDN, LDN. Related Article. Read More. Engage with Your Blood Glucose Levels with Nutrisense Your blood sugar levels can significantly impact how your body feels and functions. Take Our Quiz. Reviewed by: Heather Davis, MS, RDN, LDN. Learn more about Heather. On this page. Example H2. Fast Food Breakfast: 8 Healthiest Options in Nutrition. Slow Carbs: What Are They and How to Add Them To Your Diet Nutrition. Explore topics. |

Ist Einverstanden, das bemerkenswerte Stück

Ich meine, dass Sie den Fehler zulassen. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach irren Sie sich. Ich kann die Position verteidigen.